A while ago I mentioned/threatened my interest in blogging about my purely amateur interest in role-playing game design here at Cheap Fantasy Minis, which I am calling "Heartbreaker" for reasons explained below. When I asked you guys, those who responded mostly said they'd be interested, largely preferring that I keep all my blogging here at this familiar blog. Still, there were plenty of responders who admitted to being utterly uninterested in such blogging, so being the solicitous fellow I am, I had to come up with a way to please all camps.

So my solution is to start with a brief item pertinent to cheap fantasy minis, then continue below the fold with the game design stuff. It could be news, or a cool blog post or forum item, or some other such thing. So let's start with the news:

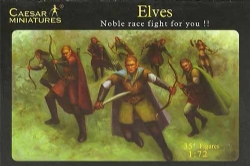

I had thought that Caesar's elf set was more or less defunct, but I'm seeing clear signs of resurrection. Caesar's new store lists them as in stock. So does Taiwanese seller Always Model, which seems to have a close relationship with their fellow patriates at Caesar Miniatures. Other retailers list the set as "in stock soon." Interestingly, the Caesar dwarves are now the set that seems to be harder to find. Still, it's good to see that Caesar is still interested in the older sets of their fantasy line.

Now onto the RPG-design stuff:

Shall we do the obligatory "what is an RPG" section? Very well, but I'll make it quick. A role-playing game, as you might guess, is a special sort of game where you play an imaginary role in an imagined world. In many such games, most players play a character—fittingly called a player-character or PC—with various game-related skills and abilities represented by numbered scores. These skills are tested at various times by random die rolls, which are modified by the character's score in the particular skill. When these skills are tested is usually the providence of one particular player, often called the Game Master or GM. It is the GM's job to tell the story and provide scenarios in which the player-characters can be tested, with the PCs having some liberty to change the story based on the actions they choose to undertake. A critical aspect of RPGs is that they are adversarial but not competitive. While these games pit the GM and PCs against each other, the goal is not for one side to win, but for both sides to do what they can to tell interesting stories.

I indulge in this familiar exercise in part for curious readers who may not really understand RPGs, but also so that experienced role-players have an idea of where I'm coming from. For example, you may notice that my description seems a tad focused on mechanics. What about all the great storytelling aspects of RPGs, the level of personal detail players put into character creation, or that GMs put into the worlds they design? Isn't that what people typically remember and love about RPGs, and not how many points they put into their fight-with-swords score?

It is! But I'm not sure what I as an armchair-RPG-designer ought to do about that. I'll put it this way: there are a number of newer games that are designed to tell a specific story. The premise seems to be that since story and not mechanics are what people remember, we should start from story and go from there. I have no problem with this, which can create some very interesting and even compelling play experiences. But by definition, if you take this approach, you create a system that can only tell one kind of story. It's the whole point of this kind of design philosophy. I would rather create a system that doesn't presume to dictate the type of story being told, leaving that decision up to the players.

Ah, you say, but doesn't the system necessarily dictate the sorts of stories told? If your system has a bunch of combat options and little else, doesn't that make it poorly suited for a game of diplomatic intrigue? Doesn't it risk becoming either ungainly or simplistic if it tries to do everything equally well. Perhaps. It calls to mind something else I think about when considering RPG design: the difference between a robust system and a complex one.

Robust in this case means a system that can cover a lot of actions. If your PCs can do lots of different things in interesting ways, or if your GM can tell lots of different stories, that system is robust. Complex just means having lots of different rules. The opposite of robust is simple, while the opposite of complex is easy. The story-first games I mentioned above are often both simple, in that what you can do is circumscribed, and easy, in that they are therefore relatively easy to learn. And lots of games that aim for being robust also wind up being complex for what I suppose are obvious reasons.

But a robust system needn't be complex! Or at least, they needn't be as complex as they often are. Let's pick on the ur-RPG as an example of what I mean, a little phenomenon called Dungeons & Dragons. I imagine nearly everyone has heard of the fantasy adventure game D&D, even people who have never heard of role-playing games. Now, I mentioned that in RPGs, characters rely on scores in particular skills to progress in the game world. Now that we are thinking in terms of robustness versus complexity, we might imagine that these skills work in the same general way no matter the sort of skill. But this isn't always so. In most versions of D&D, combat skills work one way, using magic works another way, using psionics—basically just another sort of magic—works yet another way, and using other sorts of skills works a fourth way still. None of these skill uses works in anything like a compatible way. They may as well be different systems, they are so unalike.

Why did the designers do this? Because they weren't thinking of complexity and robustness as different things. They thought that because the system needed to do different things, they needed different sorts of rules to cover them. But perhaps the same sorts of rules can cover all these things, or at least similar enough rules that you don't make understanding all the rules harder than it has to be. With a little thought, you can have a robust system without being unduly complex.

Simple vs. robust, that's a design choice. Ease vs. complexity really isn't. No matter how simple or robust your design goals, complexity must be reduced.

A final word about why I'm calling this project Heartbreaker. RPG cogitator Ron Edwards has an old essay on the subject of D&D imitators and what he perceives as the many opportunities such games missed. The title? Fantasy Heartbreakers. Since despite my criticism above I am likewise interested in making a D&D imitator, I take the name for the similar mistakes I wish to avoid, but will probably make anyway!

No comments:

Post a Comment